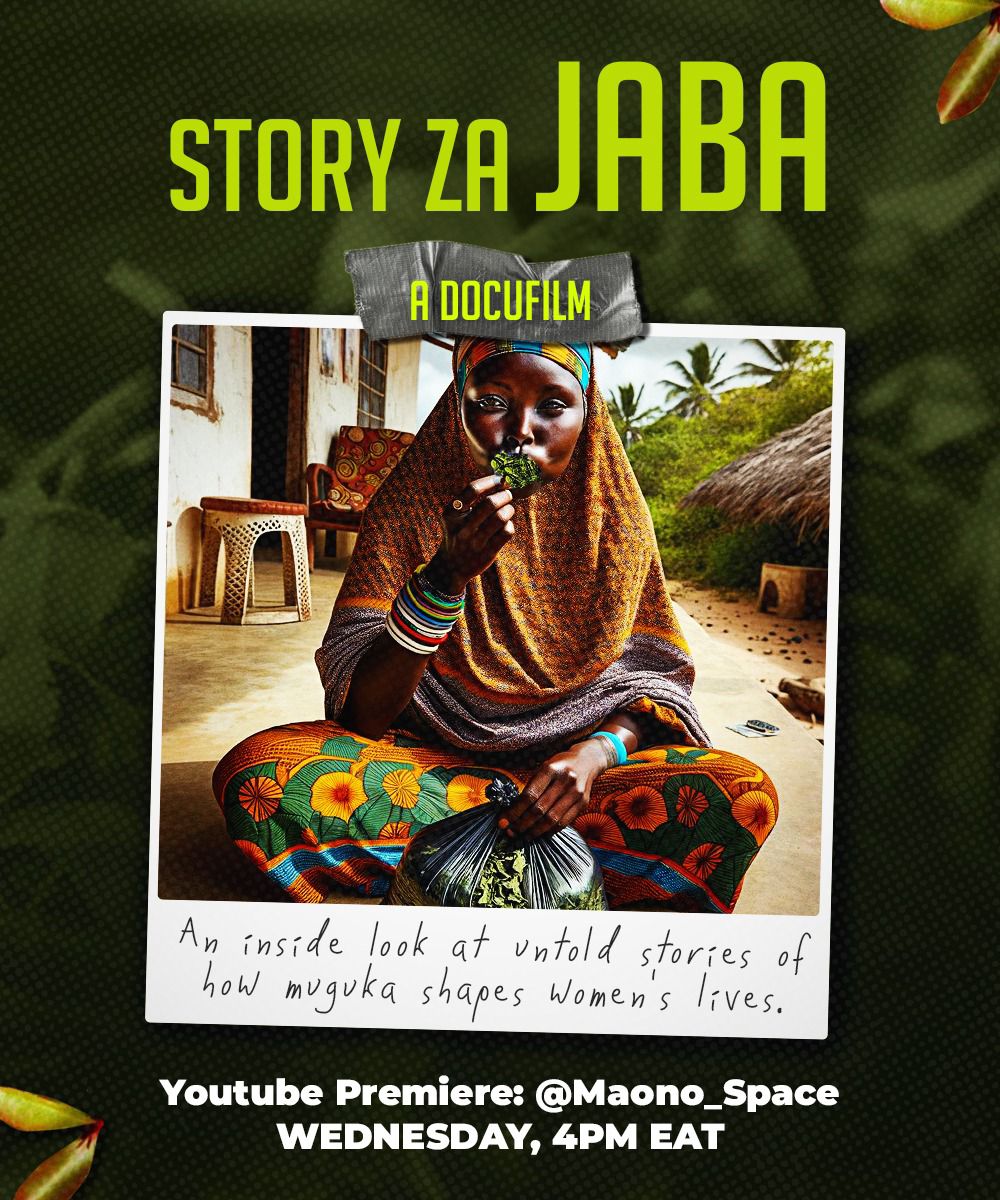

In story za jaba, a groundbreaking documentary produced by our community manager, Zeinab Zahor, we are taken on a profound journey into the world of muguka addiction in Malindi, Kilifi County, with a focus on its impact on women. This work stands as the first of its kind, delving into an issue that, despite its severity, receives little to no attention compared to other forms of substance abuse. The documentary shines a light on the often overlooked, yet deeply troubling consequences of muguka consumption, a challenge that Zeinab, having grown up in Malindi, understands all too well.

This documentary was born out of Zeinab’s personal experiences. At just 13 years old, she narrowly escaped being married off to a wealthy family friend—a plan by her own parents to finance their leisurely pursuits, specifically the consumption of muguka. This personal experience sparked Zeinab’s quest to understand the profound grip of muguka addiction that could drive parents to such lengths.

With over 300 shops in Malindi catering to this demand, it’s clear that muguka is more than just a pastime; it’s an addiction that’s deeply entrenched in the community. Zeinab’s investigation was driven by a desire to uncover the full spectrum of the muguka phenomenon, from the initial allure to the harsh realities of dependency.

Interviews with fifteen women addicted to muguka reveal the depth of the issue. These women articulate a cycle of dependence that prioritizes muguka over essential responsibilities, including taking care of their children. Despite most of them earning only around Ksh 300 per day, their addiction compels them to spend up to Ksh 800 daily on muguka and other things that they use when chewing muguka like chewing gum, cigarettes, and alcohol.

Their stories reveal various motivations for starting—ranging from stress relief and curiosity spurred by peer influence, to a desire to escape their responsibilities. However, the initial allure quickly fades into dependency, with women reporting a profound inability to function without the substance. Symptoms of withdrawal are severe, crippling their ability to lead normal lives without the constant intake of muguka.

Muguka remains unregulated, which means it can be sold at any time, to anyone, without age restrictions. Consequently, this lack of control has led to a concerning trend where even young girls and boys, as young as 10, have access to it. Sadly, because they do not have money to buy muguka, they give sexual favors to muguka vendors in exchange for the substance which may result in unwanted pregnancies and sodomy for young boys. Its social economic effects are many, including increased school dropout rates, teenage pregnancies, early marriages, sexual and gender-based violence, spread of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDs, environmental degradation, among others.

In this documentary we also learn the difference between muguka and miraa, another form of khat, noting muguka’s cheaper cost, accessibility, stronger effects, and lack of hangover compared to miraa, which may take longer to induce a high.

Through this documentary, it becomes evident that muguka addiction is a significant yet overlooked issue. It highlights the need for greater recognition and action against this addiction, akin to the efforts against other substance abuses. One interviewee, a former cocaine addict, even claims muguka is worse than crack, underlining the urgency to address this challenge.

The findings of the documentary provide a good base for more research about the effects of muguka to be done. It is a call to action urging a closer examination of the impact of muguka on people, and the exploration of potential solutions for people already addicted to it. Importantly, we hope that it sparks serious discussion about measures that can be taken to prevent younger people from getting into it.